10,000 vs 20,000 steps

There's a Landshark tweet:

10,000 steps is hailed as the daily goal, and while certainly it's good to walk 10,000 steps, it's not very hard. You should get it by accident.

20,000 steps, on the other hand, is something only a person of a different kind can achieve. They live a life distinctly different from the norm (the norm = being happy to achieve 10,000). To say "oh, you just walk twice as much" is to undermine the difference. It's not just quantitative, but qualitative.

There's something deeper here about the levels of commitment to a thing. How does this pattern repeat in other contexts?

I believe the standards we have on parenting are so low today. If you do what I consider the bare minimum (the 10,000 steps), you're "one of the good ones". If you truly want the best for your kids, you'll probably make lifestyle choices very dissimilar to the average, like not putting your kid to daycare, or homeschooling, or moving from your home. These decisions might require completely changing how your household operates, you might quit your job to commit to it. The 10k person doesn't do this, but the 20k might.

Most people who say they love traveling or food or music mean it in the 10,000 way. It tells you basically nothing about who they are. But imagine someone says they love food in the 20,000 way, now that's interesting. They probably love experimenting in the kitchen, or learning about new techniques or food customs from other cultures, and maybe they grow / hunt some of their own ingredients, too. A qualitatively different kind of person vs the normal foodie.

I think you should be hitting your 10,000 steps in many, many areas, but you must always have at least one area where you're hitting 20,000.

Learn more:

Political facts vs technical facts

"You can position facts at two poles: political facts and technical facts. A political fact is true if enough other people believe it to be true; for example, who the president is or where the border of a country is. [...] Then, on the other side, some things are purely technical. A technical fact is the result of an equation or the diameter of a virus under an electron microscope—the result of physical constants. What people think does not change technical truth. Physical facts are independent of any human being. An alien would come to the same conclusions." - Balaji Srinivasan

1+1=2 even if no one believed it. It's a truth you discover. "The New York Times is a reputable media you can trust" is a truth that can change over time. It's a truth you create.

Generally, technical facts are found in hard sciences, and political facts in social sciences. Technical facts, in business, are the actual physical performance and specs of a product, while marketing & use cases ("great for busy professionals") are political facts. In investing, many technical people express their disgust when a company is worth more than "the fundamentals" suggest, simply because they don't realize that if enough people believe the company to be worth $500m, it will be worth $500m (until they stop believing it).

Unless you work purely on hard, technical stuff, you should consciously remember that another form of "truth" exists: truth from popularity. Of course, a key to innovation and large success is knowing that this truth isn't definite. Peter Thiel's famous interview question comes to mind: "What important truth do very few people agree with you on?"

High agency, independent-minded people naturally divide the word into political and technical facts. They often find themselves asking "is this an actual, physical impossibility, or simply a social construct?" They reason forward from first principles, while conventional-minded people think backwards from social cues.

Learn more:

Variability hypothesis

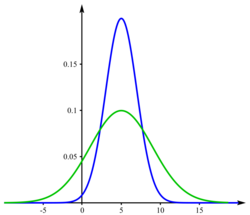

The variability hypothesis suggests that men generally have higher variation in traits than women do. So if you take a trait like IQ, you'd expect men to populate a broader spectrum than women for this trait. Note that this theory does not suggest that men, on average, would be any smarter than women; it's not a hypothesis about the mean, but about variance.

What could explain the greater variation in men? As a result of male competition for females, males need to differentiate themselves. How can you compete if you're homogeneous? So there's a mechanism for variability within males that doesn't exist to the same extent in females, resulting in males having a flatter but wider curve than females for certain traits or measurables. It's safer for nature to experiment with the Y chromosome.

As an easy example, consider that most Nobel prizes are won by men - or that most top chess players are men - and at the same time, men are much more likely to have autism, ADHD or serious reading disabilities. Another example is that the male body simply has a higher ceiling for how much muscle it can build compared to the female body, and that contributes to a larger variation in nearly all physical measurables.

Yes, in the examples there's a lot of room for controversial societal discussion. But I'll leave that aside and simply share how I apply this concept:

I have kids, both sexes. I heard someone compare raising girls to a secure office job and raising boys to a startup, and while I wouldn't be so stark about it, it stayed with me. With boys, there's a higher risk that parenting mess-ups translate into seriously bad outcomes. Most criminals are men, after all.

In the TV series Adolescence, a 13-year-old boy stabs a girl to death. The parents, after the initial shock, start pointing the finger at themselves. Could we have prevented this? Did we cause this? The father looks at their eldest, a seemingly normal teenage girl, and asks:

"How did we make her, hey?”

The mother responds:

“The same way we made him.”

--

I love all my kids equally and seek to provide everyone with all the support and possibilities they could ever need. In other words, I want to maximize the upside for everyone. But I'm just extra careful about the downside with the boys. About who they hang out with. What they do on the screens. Nipping any anti-social behavior in the bud. I reckon it's a pretty thought to say your boys and girls are all equal and your parenting style is the same regardless - and in practice you can treat all your kids the same in a lot of things! - but if you want there to be an equally small chance that you'll have major regrets about how your kids turned out to be when they're older, perhaps you need to treat them unequally in some respects.

Learn more:

Varian rule

Google's Chief Economist Hal Varian said that to predict the future, look at what the rich have now; the middle-class will have it in 10 years, and the poor will have it in another decade. Popular examples of this:

- Personal driver => Uber

- Personal chef => food delivery

- Babysitter => iPad

- Cleaner / lawn mower => robot vacuum and mower

- Home library => Kindle

- Personal assistant => AI summaries in cal / inbox (coming soon?)

A similar phenomenon happened with many big innovations, like the car, fridge or AC, though the timescale was longer than 10 years.

Tech in particular has been a democratizing force: no matter how rich you are, you cannot buy a better iPhone, or a better Google search, or a better YouTube than any middle-class or low-income person can. For the time being, the rich can buy a better nutritionist, personal trainer, or tax advisor, but sometime in the near future, tech might democratize that too, at least to a big extent.

Learn more:

- Wikipedia

- Disruptive innovation: a concept by Clayton Christensen explaining how new products often start as luxury, then gaining mass adoption by moving down the market

Idiot index

Elon's SpaceX has brought the cost of building rockets down by probably +90% compared to competitors. One of the reasons is the systemic use of an "idiot index": comparing the price of a component to the cost of its raw materials. If you're buying a valve that costs $10,000, while the steel it's made of only costs $100, you're overpaying and should find other options or manufacture in house. "If the ratio is high, you're an idiot."

A high ratio suggests overly complex design or manufacturing process, or high profit margins. With a bit of effort, you can probably find a cheaper alternative.

Ways I'm applying the idiot index:

- At the grocery store, I'm asking: "is this a reasonable manufacturing price for the product or am I being swayed by branding and packaging?" There's very little room to be an idiot when buying eggs vs a flavored drink. My rule of thumb is that the more branded or processed the product is, the higher the idiot index.

- I want as many things in my house to be solid wood as possible: furniture, doors, closets etc. That leaves me with basically three options: buy used (often old) furniture; buy the material and make it myself; or hire a woodworker. The idiot index on second hand wooden things is incredibly, incredibly low: the sofa table I'm resting my legs on was 70€ , while the wood to build something similar would easily be 300€. That's just the wood! It just makes sense to find good second hand deals; it's only the custom dimensions / use case stuff that I bother building myself.

- For many larger purchases, I usually ask if there's a second-grade product available. This way you can get much closer to the actual cost of the materials / process. Eg for my grandpa, I bought a second-grade outdoor palju, a Finnish hot tub, for 50% off. We don't care that there are minor aesthetic defects, so long as the thing works.

- For big purchases, I also want to get a quote directly from the factory, in addition to the retailer, to remove the retailer markup. Eg on wallpaper & floorboards for our renovation, the factory could give 30-50% discounts when asked, simply because that was roughly what the retailer is taking for their services (showroom, sales staff, marketing, warehousing, customer service, etc.).

- My rule of thumb with any larger purchase (appliances, renovation material etc) is that if I don't get at least 30% off, I'm an idiot.

Figure out what the price consists of & what are the parts you can influence through a bit of creative thinking or negotiation. Figure out the profit margin & try to get it close to 0. You should make it really hard for companies to make money off of you!

Learn more:

- Walter Isaacson's biography of Elon Musk

Bottom quintile effect

There’s a semi-famous (now deleted) Tweet about “the bottom quintile”, describing how much of modern society is at the mercy of this small % of problematic people.

“The rules you follow in life will be based on the behavior of the bottom quintile, the taxes you pay are to support the bottom quintile, the greatest risks to your life and property will come from the bottom quintile, the dearth of comfortable public spaces is because you have to allow the bottom quintile to be there, our zoning laws are developed for fear of the bottom quintile.”

You can consider the “bottom quintile effect” through a societal lens:

- If most societal problems are created by the bottom quintile, the job of your public education system is not so much to cater for the higher-quintile students, but to “raise the floor” and educate the bottom quintile, so they’ll stay away from trouble.

- Why people are willing to pay a premium to live in a “better neighborhood” is largely to distance themselves and their kids from the bottom quintile.

- It is very resource-heavy to support the bottom quintile (not only because they have the most problems) but because the high-ability people in the bottom quintile tend to ascend, thus leaving the bottom quintile. Resources to help the bottom quintile thus have diminishing returns over time.

Or you can consider the effect through a personal lens: since many guidelines and restrictions are created to account for the bottom quintile, you can sometimes ignore them. Probabilities based on the bottom quintile don’t necessarily apply to top-quintile people.

- The stat that 30% of marriages end in divorce does not mean your marriage has a ⅓ chance of failing, if you’re at all reasonable and put effort into the relationship.

- The rate of learning and progression at public school is built in a way that even the bottom quintile can keep up. A more gifted child - especially with a high-agency and active parent - can easily learn at 10x the pace at home.

- National dietary recommendations are created with the most unhealthy people in mind, so if you’re fit by breaking those recommendations, is that so wrong? (Related post. Related fact: the new 2024 Finnish dietary recommendations would have you eating max 1 egg per day.)

- Recommendations against co-sleeping with a baby are made to avoid negligent or drug-abusing parents from attempting it, so if you do your research and prepare your environment to be safe, you can reconsider that recommendation.

(Obviously, you cannot explain all of society through one concept. Don’t send me snarky emails. I’m aware of the limitations of this idea and underlying elitism, too - please no emails about that either.)

Learn more:

Head words vs core words

Words are just labels of a real thing, and out of the many words for a real thing, some have more potency. There are varying levels of closeness to that thing.

QC’s excellent post presents a distinction between “head words” (words felt in the head) and “core words” (words felt in the chest, or stomach, somewhere deeper). The closer you can describe a real thing, the deeper your description is felt within the body.

“Head words are civilized words, domesticated words, RLHF’d words. The part of me that learned how to generate language like this learned how to do it in school, in order to pass classes. Head words are mostly bullshit. [...]

Words that come from lower in the body are terrifying. They are a million years old. Not domesticated. Not safe for work. They have horrendous implications you could easily spend your life running away from. Taking them seriously might require you to upend everything. But they are not bullshit.”

QC didn’t give examples (deliberately, I’m sure). I hesitate whether examples ruin the concept. But I give a few not-perfect ones just to illustrate the idea:

- Partner vs beloved

- Status vs honor; valued vs esteemed; recognition vs glory

- Story vs myth

- Want vs yearning

- Darkness vs void

One core word says more than a thousand head words; this is why Hemingway’s short story cuts deeper than most novels. The most beautiful language is that which gets closest to describing the deepest emotions we have.

Core words make for great TV dialogue. Core words make for great speeches. I suspect half of the reason we find someone charismatic is because they use core words (and in doing so, speak concisely).

Head words are so easy that any AI model can do it indistinguishably from humans. It is effortless to write corporate prose and speak corporate talk all day, but notice how difficult it is to say words that come from the core. How difficult it is to describe love for your wife and children. Perhaps those words don’t exist. We say "I love them, they are my all, my greatest joys in life", but there’s more, so much more, and we just can’t verbalize it. Millions of love songs and stories try.

The realer the thing you’re trying to say - the more it is felt in the body - the harder it is to find the words.

Learn more:

Jam boy

The jam boy is an urban legend of a solution to keep mosquitoes away from golfers: a boy, covered in jam, would follow the golfers and thus keep the mosquitoes occupied. While jam boys were probably not real, similar thinking has been applied for ages, for example:

- Farmers, seeking to protect their precious crops from pests, would plant cheap crops next to it that would be more attractive to pests.

- Sacrificial anodes in ships - or your water heater - corrode first, protecting the main structure.

- Cars are designed with "crumple zones", parts of the car that take the impact of a crash to protect the passengers.

- Even in nature: Many mammals have longer, coarser guard hairs on top of their softer underfur. These guard hairs take the brunt of abrasion and moisture, protecting the insulating underfur. They might get damaged or shed, but the underfur remains intact.

A big reason why consulting companies are hired isn't because they'd bring some magical insights to the company, but because when they recommend some unpopular action like layoffs or pay cuts (which the company probably wanted to do anyway), management can shift the blame to the consulting firm.

The idea is to deliberately limit losses to something you can control, to something expendable, so that you can protect the valuable.

Learn more:

- I guess the idea of a sacrificial group is a rather common trope in Hollywood: leaving or sending a few people to die, as some distraction or delay, so that the more valuable characters can live

Anna Karenina principle

"Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way", reads the infamous opening line in Tolstoy's Anna Karenina. It reveals a general pattern in life, where an undertaking can fail in a multitude of ways, yet succeed only when everything goes right. This is called the Anna Karenina principle.

Given this asymmetry in outcomes, you could expect most endeavours that follow the Anna Karenina principle to fail. It is simply statistically more likely. But which things follow the principle?

Well, we know that things that follow the Pareto principle don't follow the Anna Karenina principle. If the 20% can contribute 80% of the results, then you can fail in almost everything but still succeed overall. If you cannot identify any factors that have outsized impact on the end result - if the result truly is a sum of everything - then the Anna Karenina principle might apply.

- Getting rich is probably not an Anna Karenina -type endeavor; randomness plays too big a part. But building a product worthy of reverence - it can only happen when everything goes right. So if you aim to just get money, apply the Pareto principle, shoot many shots, see what sticks. But if you aim at the latter, the Anna Karenina principle is the way to go.

- To feel healthy in the short term, Pareto applies: any improvement in sleep, exercise and nutrition will most likely do it. But to feel healthy in your 80s or 90s, that happens only if everything goes right (including having luck on your side).

I think it's really important to distinguish which parts of your life you can 80/20 your way through, and where you really need to obsess over every detail.

Learn more:

- Wikipedia

- Similar observation: Idios kosmos ("The waking have one common world, but the sleeping turn aside each into a world of his own.").

- Peter Thiel had this take that failure teaches you nothing, because failure is overrepresented in the realm of all possibilities. If it fails one way, it could also have failed 1000 other ways. So you could fail 50 times and still keep on failing. It's much better to learn from success, so maybe one should seek to find success, no matter how small, then scale up (vs very low probability of immediate big success).

Tangential goal trap

"The tangential goal trap: You can tell our relationship with learning is perverse when the main pursuit isn’t the action itself, but information about the action. This is very apparent in entrepreneurship: one pursues books, courses and content, rather than being entrepreneurial. There are many studying humanitarian aid for years, without actually aiding humanity – the main goal seems to be more knowledge about the field." (From my post: Information as a replacement for intelligence)

For most goals, there exists a related but distinctly different - and easier! - goal, trying to lure you away from the real thing. If we are not careful, we may fall into this tangential goal trap, thinking we're doing great progress on our goals. Indeed, usually it's easy to identify when you've been caught by the way you describe progress:

"I haven't written much yet but I set up my knowledge management system and signed up for a writing course."

"We don't have any paying customers yet but we're constantly adding features. And we just launched the company newsletter!"

Pursue the real goal, not some easy derivative of it!

Learn more:

- Paul Graham says: "When startups are doing well, their investor updates are short and full of numbers. When they're not, their updates are long and mostly words."

- Related concept: Coastline paradox

Load-bearing beliefs

In construction, a load-bearing structure is one you cannot remove, or the whole building falls down. In cognition, a load-bearing belief is one you cannot shake, or a person's whole worldview falls down.

Load-bearing beliefs are deeply engraved, seldomly reassessed. But if something does manage to topple such a belief, that's a moment when a person's life trajectory changes:

- A hard-working, career-oriented person might hold a belief that the biggest impact they can have on the world is through work. Perhaps they sacrifice their personal health and relationships for it. But then something radical might happen - like getting fired or realizing their work is net negative to society - that makes them re-evaluate their entire life (and take a year-long "spiritual journey" to Asia).

- The mid-life crisis is likely a toppling-down of the "I'm immortal" belief, a realization that you're going to die one day. When you're young, you tend to believe you have time for everything you want to do, some time in the future. But when this belief is finally disproven, a crisis ensues.

- There are load-bearing beliefs in matters of religion, namely "I believe" and "There is no God". When one is at their darkest hour, they might give up their beliefs and become anew - the stereotypical person who 'finds the light' or believes God has abandoned them.

When a person's load-bearing belief is struck down, they either rebuild themselves into something new, or they cognitive dissonance their way through, as letting go of the belief would ruin them mentally.

Learn more:

Prime number maze

Rats in a maze can be taught to turn every other time to left, or every third, or on even numbers etc. But you cannot train them to turn based on prime numbers. It's too abstract for them, the concept of prime numbers cannot be taught to a rat.

There can be a very clear, logical, simple rule to get out of the maze, and with just a bit more cognitive ability, the rat could follow it. Or at least it could be taught to follow it. But it is doomed stuck in the maze, for this particular idea is outside its conceptual range.

Likewise, what are the very clear patterns that keep us humans trapped in a maze? How could we acquire just a bit more awareness, a bit more perspective to see the simple escape from the mazes we are in?

Big revelations seem simple in hindsight, once you have developed the cognitive ability, once you have cracked the pattern. Much of life advice passed on by the elderly seems very simple to them, but often this advice is not followed by the young, for they do not see the pattern the elderly do - they only receive the words. Only via experience - via first-hand observation of the pattern - can much be learnt. But can the knowledge, the awareness nevertheless be sped up? Can you twist and turn, explore the maze, look through it with new eyes and metaphors, until you crack the pattern? And once you do, can you explain it with such simplicity that others become aware of the pattern, too?

“Once you see the boundaries of your environment, they are no longer the boundaries of your environment.”

Learn more:

- Balaji explaining the concept (originally from Noam Chomsky)

Doorman fallacy

Rory Sutherland, one of the great thinkers on behavioral economics and consumer psychology, explains the "doorman fallacy" as a seemingly reasonable cost-saving strategy that ultimately fails due to a disregard of the unmeasurable.

If you understand a doorman simply as a way to open the door, of course you can yield cost-savings by replacing him with an automated system. But if you understand a doorman as a way to elevate the status of the hotel & create a better guest experience (hail taxis, greet guests, carry bags...), then you realize the full role of the doorman cannot be replaced with an automated system.

Another example: consider a big tech company, who amid financial pressure, decides to cut spending on free lunches, bus transportation to work, on-site massage or other benefits. On paper, the company can quickly generate a hefty cost saving, but they might fall victim to the doorman fallacy. The short-term cost savings come at the expense of a brand as an employer who provides unrivaled employee perks and places employee satisfaction over investor satisfaction, and the long-term damage to attracting new talent and retaining current employees may cost the company a lot more in the years to come.

You can think of the doorman fallacy as an extension or example of the Chesterton's fence fallacy: getting rid of the fence (doorman) without fully understanding why it was there in the first place.

Learn more:

- Signaling theory

- Book: Alchemy by Rory Sutherland

Levinthal's paradox

Levinthal's paradox is that if we tried to predict how a protein folds among all decillions of possibilities, it would take us an astronomically long time. Yet, proteins in nature fold in seconds or less. What seems impossible to the human, paradoxically, happens all the time in nature, without us understanding how it is possible.

The paradox is a reminder about nature's immense "wiseness" and our lack thereof in comparison. Nature finds a way, even if we cannot see how. Often, then, the default action for us should be inaction, to let nature do its thing with minimal human intervention. (Related: iatrogenesis)

One can try to chase longevity with a diet of pills, an army of scientists tracking every possible thing about their body, an insane daily routine… Only to be outlived by a random rural person just trying to build stuff with their own hands and eating what they grow or hunt - as nature intended.

Even with constantly improving technology and theory, we ought to be humble and appreciate that nature might be smarter still.

(Note: Since the paradox was proposed, AI has advanced our understanding of protein folding dramatically.)

Learn more:

Coastline paradox

You'd think it would be easy to define the length of a coastline of any given country. Just look at the map and measure the length of the coast, right?

Turns out, it is notoriously difficult to measure this. The closer you look, the longer the coastline.

At what point do you stop zooming in? The problem is fractal!

Many problems in personal life or business possess a similar quality. Seemingly straightforward at first, but increasing in complexity the more you look at it. For example, say you want to be healthier. How should you exercise? How often and when? Should you take supplements or vitamins? What is best for your unique body composition or genetic tendencies? Or if you want to write content online, you can research all the keywords, best website builders, headline formulas, writing advice from gurus, note-taking approaches and tools... until the point where you spend 5% of your time writing and 95% zooming in on the problem!

Suddenly you're overwhelmed and won't even start.

The solution? Just go for a decent ballpark - the 80% solution - and stop overanalyzing. In the health example, just sleep more, move more, eat better, and forget about the small stuff. Don't get sucked into the fractal.

Learn more:

- Wikipedia for the Coastline paradox and fractals

Quantum Zeno effect

The Quantum Zeno effect is a quantum physics application of one of Zeno's paradoxes, proposed by the ancient Greek philosopher, whereby if you observe an object in motion at any given time, it doesn't appear to be moving. And since time is made of these infinitely short snapshots of idleness, there can be no motion.

Of course, motion exists and this is philosophical nonsense, but thanks to it, we have a cool name for the Quantum Zeno effect, which states you can slow down a particle's movement by measuring it more frequently.

The same idea can be applied more widely:

- The more often you look at your investment portfolio or any analytics, the less changes. If you come back a month or a year later, then things have changed - so what's the purpose of looking daily?

- You cannot see the effects of your exercise programme in the mirror, but you can in a photo taken 5 months ago.

- The more often you check on progress with your team, the more you interrupt their work with reports and check in meetings, thus slowing down progress.

Learn more:

- Wikipedia

- Hawthorne effect: worker productivity changing when observed

- Demand characteristics: subjects of psychological experiments responding or behaving differently because they know they are studied

Enantiodromia

Enantiodromia is an idea from Carl Jung that things tend to change to their opposites, that there is a cyclical nature between things.

- "Hard times create strong men, strong men create good times, good times create weak men, and weak men create hard times"

- The more authoritarian a government, the more it gives rise to a rebellious movement

- We use antibiotics to kill bacteria, which leads to the extreme, antibiotic-resistant bacteria

- When you're dying of cold, you get a feeling of warmth; when you're really hot (like in a sauna), you might suddenly feel cold as your body adapts to the heat

- If there was an extreme of something in your childhood, that might give rise to the opposite in adulthood

- Cultural trends: Girlbossing vs trad-wifing, the "feminine" man vs "masculine" man ideals, an excess of rationality and modernism leads to wistful thoughts about the old ways...

- “The empire, long divided, must unite; long united, must divide”

When there's a dominant trend, there is always a counter-trend. A mainstream opinion and the contrarian. Shift and countershift.

Learn more:

- Wikipedia

- Horseshoe theory: the political idea that the far-right and far-left resemble each other, rather than being polar opposites

Rohe's theorem

Rohe's theorem: "Designers of systems tend to design ways for themselves to bypass the system."

Or more generally: those who create or advance a system seek to prevent themselves from being exposed to it, perhaps as they have intimate knowledge of the faults or the predatory nature of the system.

Examples:

- Government officials can exempt themselves from certain rules that other citizens must abide by

- Big tech employees who block or limit the social media usage of their kids / want to move “off the grid”

- (Fast food) restaurant workers who rarely eat out

- Doctors who prescribe medicine but don't let their kids eat meds

- Teachers who homeschool their children

- Insurance company workers who don't have insurance themselves

In some cases, the following sayings relate: "never get high on your own product" and "Those who say the system works work for the system."

Learn more:

- Book: The Systems Bible by John Gall

Ostranenie

Ostranenie (also known as defamiliarization) is about presenting familiar things in unfamiliar ways, in order to generate new perspectives or insights. One could argue that most art aims at this.

Stark example: a movie where the roles of men and women are swapped, so the viewer becomes more aware of the gender roles of the present.

Subtle example: any argument or idea that is presented with the help of a story or metaphor. A speech that just says "work hard, overcome obstacles" is boring and uninspiring, as it is nothing new, but a movie about a successful person who worked hard and overcame difficulties is inspiring, as it brings a new frame to the idea.

I suspect modern books are full of 10-page examples and stories for this reason. They don't have any new ideas, so they settle for stories. (A cliché reframed can be a revelation, though, but it requires more from the artist.)

Anything can be a line for a great comedian because they can describe it in a funny, new way.

Learn more:

- Wikipedia

- There are pretty popular artists whose main premise is ostranenie, for example Strange Planet

Gardener vs carpenter

Alison Gopnik observes two opposing parental methods: the gardener and the carpenter. The carpenter tries to lead the child to a "good path", crafting them into a well-functioning human being, using all the parenting tricks in the book. A gardener is more concerned with creating an environment where the child can develop safely and healthily, and letting the growth happen organically.

Carpenter parenting is one-way, where the adult molds the child into what they believe is best. Gardener parenting is interactive, where the adult creates the conditions in which the child can become themselves. Every parent knows that if you try to "force teach" something to a child, they will probably not learn it, but if you let them learn it themselves....

We underestimate how wise nature is. A child is the most effective learner in the world, by design - so let them learn on their own, instead of giving instructions they don't need, and trapping their minds in the process. By ascribing age-appropriate activities and scheduling the child's weeks like they were on a training camp, you rob them of their own autonomy and creativity. You can do more harm when you try harder!

A bird doesn't need a lecture on flying, and a child doesn't need you to explain how to play with cubes or a cardboard box. Where else are we trying so hard, when we probably should just relax a bit and let nature do its magic?

Learn more:

- Book: The Gardener and the Carpenter by Alison Gopnik

Thermocline of truth

In large organizations, the key to succeeding is to do great work. Or, at least, to appear so. That's why the culture might seem fake: everyone is doing super-amazing, everything is roses and sunshine!

This is due to the thermocline of truth effect, whereby people tend to report only on the positives and hush down on the negatives. Like warm water rises up and cold stays at the depths, upper management believes everything goes great while the people who do the work know better.

It is hard to resist this effect, as everyone has an incentive to appear successful to their peers and managers. Therefore, things inside an organization resemble a watermelon: green on the outside, red on the inside.

Learn more:

Diseases of affluence

As you get wealthier, your life tends to get more comfortable. And as you remove some discomforts, certain diseases take their place. While wealth or affluence isn't the real cause - behavior is - you may have noticed some of these patterns:

- More income > eat out / take-out more > restaurant food is often unhealthier than home-cooked > diseases of affluence

- Don't feel like cleaning / mowing the lawn > more income means now you have a choice to hire someone > lose opportunities for exercise > diseases of affluence

- Buy car / electric bike instead of cycling, or walking to the public transport > diseases...

Even if you could afford to live more comfortably, should you?

"Advancements to make our lives less physically taxing have taxed us physically." - Katy Bowman

Learn more:

- Wikipedia

- My related post on variation

- Uneconomic growth: economic growth that decreases quality of life

Precautionary principle

New things tend to be, by default, risky because limited evidence exists as to their full consequences. The precautionary principle is to remain skeptical and cautious of things that may have significant consequences, especially as some might be hidden and currently unforeseen.

The general idea is that when you change or add something, you introduce complexity, and we usually cannot predict all the results of this complexity. So there should be strong evidence or reason for change, otherwise the potential negative results may overweight the positives.

Consider that your friend recommends you stop eating meat and take in your protein in the form of insects instead, for ecological reasons. The precautionary principle here would have you question this recommendation, given the health impacts of meat consumption are known but the impact of insect consumption at big portions isn't.

Yes, you may receive the same amount of protein, but you would introduce significant change to the enormously complex system that is the body, so there are likely to be hidden consequences. Some of them might be positive, some disastrous, or maybe everything would be fine - we don't know!

The precautionary approach doesn't necessarily mean you're "stuck in your ways", never try new things and never innovate. Rather, it's a more risk-averse approach at trying new things and innovating; perhaps a more humble way to do things, as you appreciate the limits of human knowledge amid vast complexity.

Learn more:

Hysterical strength

Hysterical strength is the (anecdotal) observation that people have superhuman strength when under intense pressure. For example, an otherwise normal person being able to lift a car to save their family member who got stuck under. Hysterical strength is the "break in case of emergency" of human anatomy.

The implication here is that we have a huge reservoir of strength that we cannot tap into under ordinary consequences. Why? Possible explanations:

- Self-protection: we are strong enough to accidentally break our bodies if our strength isn't regulated, so there might be an unconscious "Central Governor" who protects us... from ourselves.

- Energy-conservation: if we could use 100% of our strength at will, would we have the strength when we really needed it? It's evolutionarily smart to always leave a bit of gas in the tank, just in case.

You can apply the idea to mental strength as well (sometimes called "surge capacity" in this context). You can work scarily hard when it's required of you. Today you think you're working your hardest, and next week multiple life stressors hit simultaneously, you must push through, and you realize you had probably double the capacity than you think you had.

But like with your body, there's probably a good reason why we cannot use this strength at will, at least easily. Intense stress causes mental damage like burnout and dissociation, similar to how intense physical stress leads to torn muscles and tendons.

How can knowledge of hysterical strength's existence benefit us?

- Use constraints smartly to make progress faster than you thought possible. If you want a clean home, invite everyone over in 2 days. If you want to finish your presentation, schedule a meeting with your director for next week.

- You don't need to give up when your body tells you to. If I'm shoveling snow or chopping wood and I get tired, I know I have at least 2 hours left in me. (Just don't get injured in the process.)

- Take on bigger challenges, your mind and body can probably handle it. Just ensure you get enough rest after.

Many people who have been "tested" are in part happy about it, as they now know what they are capable of. It brings confidence to know that you are much stronger than you think.

Learn more:

Copyright trap

A copyright trap is usually a fake entry in one's original work, designed to trap copycats. If their work also has the fake entry, that means they copied your work - how else would they have the same fake information?

This technique can take many forms. A mapmaker can include a non-existent street or town. A dictionary can have fake words, while a telephone book could have fake phone numbers. A book could reference academic articles, facts or experts that don't exist.

(There are other cool, related instances like people who make rugs manually sometimes purposefully add a tiny flaw, to prove the rug was created by hand, not by a machine. Will something similar happen to writing – adding elements that the reader could fairly reliably assume an AI would not add?)

Elon Musk famously used a related technique, a canary trap, to find a Tesla leaker:

Learn more:

Kolmogorov complexity

Kolmogorov complexity measures the randomness or unpredictability of a particular object.

Consider the following strings of 20 characters:

- jkjkjkjkjkjkjkjkjkjk

- asifnwöoxnfewäohawxr

The first string has lower complexity, as you could describe the string as "write jk 10 times", while the second string has no discernable pattern, so you could only describe it as "write asifnwöoxnfewäohawxr".

You could assess the originality or quality of information via this type of complexity. For example, the shorter the book summary, the worse the book. If you can cut down 99% of the length while still containing the same key information, that tells something about the quality of the book.

By contrast, the longer the book summary, the better the book, as it implies there are more unique ideas that are taken to a greater depth, warranting more time to explain them properly.

Can you guess where a friend or colleague will be in 5 years? The more details you reveal about the person, do they seem to follow a pattern (jkjkjk) or does each new sentence surprise you a little bit? Kolmogorov complexity, in a person, is often a sign of high-agency, independent thinking.

Learn more:

Nutpicking

Nutpicking is a tactic to make the opposing side seem wrong/crazy.

Step 1: Pick the craziest, most extreme example or person from the opposing side

Step 2: Claim that this example/person represents the entire opposing side. Therefore, the entire enterprise must be crazy!

Of course, an extreme example doesn't represent the entire group - that's why it's an extreme example. But some have a hard time realizing this. If you see the nutpicking tactic being used, probably best to exit the conversation.

Learn more:

Semantic stopsign

A semantic stopsign essentially says: "Okay, that's enough thinking, you can stop here". It's a non-answer disguised as an answer, with a purpose to stop you from asking further questions and revealing the truth.

Imagine your friend claims you should rub mud on your face before heading outside, as it will protect your skin from the sun and keep it hydrated.

"Mud? Are you crazy? Why would I do that?"

"It's recommended by scientists."

"Oh... well in that case."

That's a semantic stopsign. It's not actually giving you an answer for why you should rub mud on your face, rather the purpose is to stop you from asking more questions.

Learn to recognize these stopsigns and disobey them. Often the reason someone presents you with a semantic stopsign is because there's an uncomfortable truth close by. When a politician is asked a tough question and they answer "to defend democracy" or "to fight terrorism", they aren't really giving you an answer - they are saying "okay, that's enough questions, you can stop here".

When someone hits you with a stopsign, your natural reaction is to obey and move on. Next time, do the opposite and see where that leads.

Learn more:

Mean world syndrome

You may think the world is more dangerous than it is, as you've been consistently exposed to news about crime, violence and terror.

One may rationally know that the news is mostly about the extraordinary (the ordinary is rarely newsworthy), yet still unconsciously have a biased view of the world as a dangerous place.

Remember that for every instance of danger, another of kindness exists - though it's probably not televised. I believe whether you are pessimistic or optimistic is mostly a question of how well you understand this idea of unlimited evidence and limited portrayal.

Learn more:

Politician's syllogism

The politician's syllogism is of the form:

- We must do something.

- This is something.

- Therefore, we must do this.

Similar form:

- To improve things, things must change.

- We are changing things.

- Therefore, we are improving things.

Watch out for this fallacy in politics but also in corporate speeches and work meetings. The lure of acting is strong, even if sometimes not intervening might be for the best. Suggesting inaction rarely ends well in politics/business, hence the existence of fallacies like this.

Learn more:

Fruit of the poisonous tree

Fruit of the poisonous tree is a legal metaphor used to describe evidence that is obtained illegally. The logic of the terminology is that if the source (the "tree") of the evidence or evidence itself is tainted, then anything gained (the "fruit") from it is tainted as well. Therefore, one may not need to refute the evidence, just prove that the evidence was gained illegally.

Similarly, at least in my mind, if you get money or fame in the wrong way, it doesn't count. The success becomes tainted and ceases to be success.

Learn more:

Autopoiesis

The term autopoiesis refers to a system capable of producing and maintaining itself by creating its own parts. A cell is autopoietic because it can maintain itself and create more cells. Imagine a 3D printer that could create its own parts and other 3D printers.

An autopoietic system is self-sufficient, thus very robust. Some people describe society and communities as autopoietic, maybe even describing bitcoin as an example of autopoiesis. But forget about following definitions too strictly for a second. If you apply the concept of autopoiesis liberally to your life, does it change how you shape your environment and lifestyle, your "personal system"? Does it help you become resistant to external circumstances?

I want to have as tight a hermetic seal in my life as possible:

- Build my house and furniture from wood that grows in my backyard. If anything needs repairing, I already have the material.

- Eat what I grow from my land, and use any food waste as compost for the land to create more food. (Or feed excess apples and crops to deer that I hunt for meat.)

Learn more:

Affordances

A crucial part of human learning is understanding how to interact with the environment. Designers of objects can make this easier for us. An affordance is a property or feature of an object that hints what we can do with the object.

- If a cord has a button on it, you push it. If a rope hangs from a lamp, you pull it.

- If the door has a knob, you turn it. If it has a handle, you press it down. If it has a metal plate and no handle, you just push the door.

- If a word in an article is blue, you can click on it and be taken to a different page.

When you take advantage of affordances, people know what to do. No instructions needed. The less you need to explain, the better the design.

Learn more:

Fredkin's Paradox

Fredkin's Paradox states that "The more equally attractive two alternatives seem, the harder it can be to choose between them—no matter that, to the same degree, the choice can only matter less."

If you had two really different options, it'd be easy to choose between them. But when they are similar, choosing becomes difficult. However, if the two options really are similar, it shouldn't matter too much which you choose, just go with one. The impact of choosing one over the other will be so small that any more time spent analyzing is time wasted.

Because of Fredkin's Paradox, we spend the most time on the least important decisions.

Learn more:

Fosbury Flop

Before 1968, there were many techniques that high jumpers used to get over the bar, though with most, you'd jump forward and land on your feet. Then Richard Fosbury won the Olympic gold with his "Fosbury flop" technique which involves jumping backward and landing on your back. Ever since, the Fosbury flop technique has been the most widespread and effective technique in high jumping, and in fact, it's the technique you have probably seen on TV if you've watched high jumping.

A Fosbury Flop moment happens to an industry or area when a new innovation, approach or technique is introduced that then becomes the dominant option. These are breakthrough improvements that change the course of history.

Learn more:

First penguin

When penguins want food of the fishy kind, they may need to jump off an iceberg into the water. The problem is that they can't see what lies beneath - a predator might be waiting for a herd of penguins to fall straight into their belly. The group of penguins needs to decide whether to find food elsewhere or jump into the unknown.

This is where the "first penguin" (sometimes called "courageous penguin") stands up. They take one for the team and jump off the cliff, while the rest wait to see whether the water is clear. The first penguin takes a huge personal risk to ensure the survival of the group.

Entrepreneurs and risk-takers take a similar leap into the unknown, perhaps with even worse odds. While each risk-taker may not survive (for example, few startups succeed), the world is a better place because these risk-takers exist.

Learn more:

Expected historical value

Paul Graham wrote on Twitter:

"Let's invent a concept.

Expected historical value: how important something would be if it happened times the probability it will happen.

The expected historical value of current fusion projects is so enormous. I don't understand why people aren't talking more about them."

This concept, though similar to the original concept of expected value, puts a spin on it. Expected historical value is a concept to assess the future importance of things today.

What thing today could become "history" in the future? Sure, it may not get much attention now, but could it be recognized by the future as ground-breaking? What innovation, technology or idea, little discussed today, will be discussed a lot in the future?

There's a personal life spin on this as well: What experience or moment today could become a fond memory 50 years from now? It may not be the moments you'd expect (like a fancy trip) but an ordinary moment (like going for a midnight swim).

Learn more:

Confusopoly

A confusopoly is an industry or category of products that is so complex that an accurate comparison between products is near-impossible.

If you try buying a mobile phone from a teleoperator, you have unlimited options between phone tiers and texting and data limits. Or if there's a new video game launching, you could get an early-bird version, or the early-bird collector edition, or just the collector edition, or maybe a deluxe version which has some features of the other options but not all of them. If you try to buy insurance or banking/finance products, the options are so confusing that you're just inclined to choose one at random and stick with that for life.

My favorite example is toilet paper. Different brands have a different number of rolls in their packages, and they may have a different amount of paper in each roll, and maybe they'll have a value pack, but the normal pack may have a "get 1 roll free" promotion, but the other brand has a 20% discount, and then there's the matter of softness and thickness... In the end, you just give up and go with the most visually pleasing packaging.

Learn more:

Applause light statements

An applause light statement is designed to gain the support or agreement of an audience, the same way an actual applause light or sign indicates to the studio audience that this is the part where you should start clapping.

Usually there isn't much substance behind an applause light statement, and you can spot this by trying to reverse the statement. Consider someone saying "we need to ensure technology benefits everyone, not just a few people". If you reverse it, you get "we need to ensure technology benefits a few people, not everyone". Since the reversed statement sounds odd and abnormal, the original statement is probably conventional knowledge or the conventional perspective and doesn't contain new information. The statement isn't designed to deliver new information or substance, just to gain support.

Too many applause light statements is a characteristic of empty suit business talk, the "inspirational speaker" and the charismatic politician. Very little substance, merely an attempt at influencing perception. Sometimes, though, applause light statements can be useful, like when you want to establish common ground or set the stage for an argument. But most of the time, these statements are used merely as the "easy way" to write a speech and influence an audience.

And yes, applause light statements are more common in speech than in writing. In writing, the reader has more time to process what you said and call you out if you have zero substance behind your words. In speeches, you don't have this luxury, and it's pretty hard to hold a negative opinion of a speech if everyone else around you was nodding and applauding the entire time.

Eliezer Yudkowsky, who coined the term, wrote a tongue-in-cheek speech using only applause light statements. It looks eerily similar to just about every speech I've ever heard:

"I am here to propose to you today that we need to balance the risks and opportunities of advanced artificial intelligence. We should avoid the risks and, insofar as it is possible, realize the opportunities. We should not needlessly confront entirely unnecessary dangers. To achieve these goals, we must plan wisely and rationally. We should not act in fear and panic, or give in to technophobia; but neither should we act in blind enthusiasm. We should respect the interests of all parties with a stake in the Singularity. We must try to ensure that the benefits of advanced technologies accrue to as many individuals as possible, rather than being restricted to a few. We must try to avoid, as much as possible, violent conflicts using these technologies; and we must prevent massive destructive capability from falling into the hands of individuals. We should think through these issues before, not after, it is too late to do anything about them..."

Learn more:

Conjunction fallacy

When something is more specific, more detailed, we tend to think it is more probable, even though specific things are actually less probable. This is the conjunction fallacy - not understanding that there is an inverse correlation between specificity and probability.

For example, consider your standard marketing prediction article - they'll say something like "next year, more will be spent on digital advertising as big companies finally shift their TV budgets to online channels". This may sound logical, but, of course, it is more likely that the companies will spend more on digital advertising next year for any reason vs for one specific reason.

Details place your mind and gut against each other: your gut wants to believe the narrative because it sounds more believable with all those details - you can follow the steps to the conclusion. But your mind should realize that the more specific the prediction or narrative, the less you should believe it.

Imagine someone - perhaps a billionaire or someone with a big Twitter following - explaining their success. The more specific the "blueprint" they claim is the reason for their success, the less probable it actually is that their success can be attributed to it. The secret formula for their success sounds more convincing as they add detail, but it also becomes less probable as the actual cause for their success. Kind of defeats the purpose of buying their "7-step framework" master course, no?

Learn more:

- Wikipedia

- Conditional probability

Wittgenstein's Ruler

If you're measuring your height with a ruler and it shows you're 4 meters tall (13 feet), you gained no useful information about your height. The only information you gained is that the ruler is inaccurate.

Wittgenstein's Ruler is the idea that when you measure something, you are not only measuring the measured (your height), but also the measurer itself (the ruler). You might be getting more information about the measurer than the measured!

Another example: the fact that an employee you know to be brilliant receives a mediocre performance rating doesn’t necessarily mean they are mediocre, it could simply mean the performance rating process is broken.

Learn more:

- Wikipedia

- Similar concept: Twyman's law

Potemkin village

A Potemkin village is a country's attempt to signal that it's doing well, even though it's doing poorly.

Wikipedia: "The term comes from stories of a fake portable village built by Grigory Potemkin, former lover of Empress Catherine II, solely to impress the Empress during her journey to Crimea in 1787. While modern historians agree that accounts of this portable village are exaggerated, the original story was that Potemkin erected phony portable settlements along the banks of the Dnieper River in order to impress the Russian Empress; the structures would be disassembled after she passed, and re-assembled farther along her route to be viewed again as if another example."

Consider a more modern example of Turkmenistan's capital city, Ashgabat, with enormously expensive buildings, hotels, stadiums, indoor ferris wheels and 18-lane roads... that no one uses. Or consider how during the 1980 Olympics in the Soviet Union, they had painted only the road-facing walls of houses on the way to Moscow. Why bother with the entire house when one wall creates the perception? Similar stories exist from newer Olympics; global events are a juicy opportunity for government signaling.

The term Potemkin village has been used more metaphorically to refer to any construct aimed at signaling you're doing well when you're not. For example, consider a creator trying to signal that their newsletter is doing well - they'll talk of "readers" and visitors to their website and other Potemkin metrics, but they won't talk of subscribers or money.

Learn more:

- Wikipedia

- Kayfabe is a related term. Both linked with politics and perception.

- Simulacrum

Moloch

Moloch is many things:

- In religion, Moloch is an ancient god of child sacrifice, one who would trade power and triumph for your child.

- In Allen Ginsberg's poem, Moloch is an entity of sorts, an all-encompassing force that perpetuates chaos and misery in our world.

- In a famous essay by Scott Alexander, Meditations on Moloch, Moloch is used as a metaphor for both of the above: a god-like, intangible force that upholds faulty systems by making us sacrifice what we love most for a bit of competitive advantage. An invisible hand that prevents us from improving certain systems.

Everyone can recognize that a system is faulty. The education system prioritizes all but education. We spend billions on the military that could be spent on healthcare. Why?

Not because we wouldn't notice that these things are broken, but because of an invisible force - Moloch - that prevents us from improving them.

People ask why we can’t reform the education system. But right now students’ incentive is to go to the most prestigious college they can get into so employers will hire them – whether or not they learn anything. Employers’ incentive is to get students from the most prestigious college they can so that they can defend their decision to their boss if it goes wrong – whether or not the college provides value added. And colleges’ incentive is to do whatever it takes to get more prestige, as measured in US News and World Report rankings – whether or not it helps students.

If only there was an entity so powerful that it could change the incentives, all at once. But we don't have one, so every individual is better off playing by the system, even if everyone hated it. Moloch is a coordination problem: Everyone acting rationally in their own self-interest leads to a bad outcome for everyone involved.

Moloch is also the reason why people can easily seem hypocritical when they're not. One can criticize and loathe the capitalist system, yet live by its rules and even pursue success in that system. Yes, it would be more honest and virtuous to try to exit the system - but how would that be rewarded? Does that feed the kids? You swear you'll never start posting cringey LinkedIn posts about your half-marathon and 5 lessons learned, but your co-workers that did are now your managers, so you let go of your values and start twerking for the dollar, even if it kills you inside.

The more you look at the systems around you (education, healthcare, workplace, modern dating, social media algorithms...), the more you see Moloch.

Learn more:

- The famous post by Scott Alexander: Meditations on Moloch. One of those that instantly makes things click in your head.

- Zugzwang

Charitable interpretation

Imagine someone presents an argument to you. You have roughly two ways to interpret it:

- Charitable interpretation: Consider the strongest, most solid version or implication of the argument. You start by assuming that the argument might be true, and you try your best to see how it could be.

- Uncharitable interpretation: Consider the weakest possible version of the argument. You start by assuming that the argument is wrong, and you try your best to confirm this assumption.

Open-minded people generally interpret what they hear charitably while close-minded people stick to what they think is right and don't bother entertaining other arguments. An open-minded person asks "how could this be right?", a close-minded person asks "how is this wrong?"

Especially on Twitter, snarky repliers will interpret your tweet in the least favorable way possible, identify a weakness in your tweet (which is easy when you've already weakened the tweet with your interpretation), then feel smart when they point out that weakness to you. Of course, everyone else thinks them a fool.

It would make one seem much smarter if they interpreted the tweet in the most charitable way possible, then identify a weakness in it and express it clearly.

Learn more:

Rare enemy effect

The rare enemy effect is a niche but interesting phenomenon in predator-prey interactions.

Consider the case of earthworms. Their number one enemy is the mole (a mole eats almost its body weight in worms each day). So the worms have adapted to recognize an approaching mole by sensing the vibrations of its feet as they dig in the soil. When they sense it, the worms escape to the surface, where mole encounters are unlikely.

However, other predators of worms have figured this out. For example, seagulls perform a "dance" to vibrate the ground, bringing up unwitting worms to the surface, ready for snacking. Wood turtles do a similar thing. Humans, in a process called "worm charming", plant a stick into the ground and vibrate the stick to summon the worms, often to collect them for fishing (but some do the process for fun and sport).

The rare enemy effect happens when Predator A exploits the prey's anti-predator response to Predator B (the main predator). It must be that Predator A is a rather rare encounter to the prey (hence the name of the effect); if they were a main predator, the prey would eventually develop an anti-predator response to them, too.

If you look closely, you can see a similar effect in the human realm, too:

- One (rather known) trick burglars may perform on you is very similar to what seagulls do. Imagine a man in a suit knocks at your door, informing you that burglars have been spotted in this neighborhood. But you can protect yourself by buying his company's security system. Worry not - before you commit to anything, he can do a free security assessment right away, inspecting potential points-of-entry (and where you keep your valuables). Your anti-predator response is to protect yourself from the burglars, so you let the man in. Whether you sign any contracts or not, you may find your house broken into within a few days.

- A similar scam happens digitally all the time. You receive an email, saying that your passwords or information security is in danger, and scammers can steal your money or data if you don't act. Of course, acting in this case means paying another scammer, or giving him access to your or your company's accounts, where he will change all passwords and require ransom to let you back into your own systems.

- Naturally, there are legal forms of exploiting one's anti-predator response, namely fear-mongering advertisements or the exaggerating (real) door-to-door home security salesman.

And do not think that these processes are limited to capturing your money; they want your support, information, attention and time, too. If there's a predictable anti-predator response, there's someone who exploits that response, legally or illegally.

Learn more:

- Another example of the rare enemy effect in nature

Shibboleth

A shibboleth is a word or a phrase that distinguishes one group of people from another.

Wikipedia has many examples (some rather funny):

- Some United States soldiers in the Pacific theater in World War II used the word lollapalooza as a shibboleth to challenge unidentified persons, on the premise that Japanese people often pronounce the letter L as R or confuse Rs with Ls. A shibboleth such as "lollapalooza" would be used by the sentry, who, if the first two syllables come back as rorra, would "open fire without waiting to hear the remainder".

- During World War II, a homosexual US sailor might call himself a "friend of Dorothy", a tongue-in-cheek acknowledgment of a stereotypical affinity for Judy Garland in The Wizard of Oz. This code was so effective that the Naval Investigative Service, upon learning that the phrase was a way for gay sailors to identify each other, undertook a search for this "Dorothy", whom they believed to be an actual woman with connections to homosexual servicemen in the Chicago area.

- In Cologne, a common shibboleth to tell someone who was born in Cologne from someone who had moved there is to ask the suspected individual, Saag ens "Blodwoosch" (say "blood sausage", in Kölsch). However, the demand is a trick; no matter how well one says Blodwoosch, they'll fail the test; the correct answer is to say a different word entirely; namely, Flönz, the other Kölsch word for blood sausage.

In many professions, one may have shibboleths as well, to distinguish those who are more experienced or knowledgeable from those who are not. These may not be used in a password-like manner, rather in a manner like this: "If they use certain words or concepts correctly, it's safe to assume they aren't new to this field".

Other times, shibboleths are used as signals of one’s belonging to or belief in a cult – like “wagmi, gm, fud, diamond hands” in the NFT/crypto space.

Learn more:

- Wikipedia

- Forensic linguistics is a field of interest since the words someone uses can be tied to which group they belong to

Relevance theory

Relevance theory explains why a word or a phrase can convey much more information than its literal version. For example, imagine you own a really bad car - it breaks down often, looks ugly and it can barely hold itself together. You swear you'd demolish it yourself if only you had money to buy a new one. Your neighbor asks what you think of your car and you say "Well, it's no Ferrari". What you communicate is very little, but they understand the message.

The reason we can convey more than we say is self-assembly. When something is being communicated to you, you add relevant information from the context to that message (who said it to you, how they said it, who else is there, what has been said before, previous experiences...) until you arrive at the final message. So only a small part of the intended message needs to actually be said explicitly, everything else can happen due to self-assembly. Just think of an inside joke - one word can be enough to convey an entire story.

Once you understand this effect, you have a framework to understand different types of communication.

For example, a good joke gives away a strong enough connection that you understand what is meant, but the connection must be weak enough as not to ruin the punchline. A joke where the connection is too strong isn't fun because you can guess the punchline; there is very little self-assembly required by the receiver of the joke.

A good aphorism (or good advice) gives away a practical enough idea that you can apply it to your own experiences, but it must be abstract enough that you come up with the application yourself. Consider very wise advice: it's never straightforward "do-exactly-like-this" communication, you usually need to decipher the message, to construct your own meaning of it. It's more impactful to make you realize what to do yourself than to tell you exactly what to do.

In advertising, there is an incentive to communicate the most with the least amount of information or time. The bigger portion of the message can be outsourced to the context, the better for the advertiser, since now the receiver of the information does more self-assembly in their heads. This leads to a sort of mental IKEA effect where they'll enjoy your message more, now that it isn't pushed into their heads, but when they themselves are a co-creator of that message.

Generally, the smaller the ratio of what is communicated to what is understood, the better the aphorism, advice, joke, tagline or ad.

Learn more:

- Wikipedia

- Inception (Planting "seeds" into someone's head. Plus, it's a good movie)

Category thinking

You're engaging in category thinking when, instead of trying to solve one problem, you try to solve a whole category of problems.

For example, in computer security, you can look at risks within individual systems, or you can look at risks within an entire category of systems, for example, every system that uses Log4j. You can consider what happens if one autonomous vehicle got hacked, or you can consider what happens if all of them were hacked simultaneously because of a security issue affecting every autonomous vehicle.

In your personal life, you could tackle all of your health problems individually, maybe buying medicine for one problem and changing your diet to tackle another problem. Or you could address the entire category by minimizing evolutionary mismatch, to live more like humans have evolved to live.

Category thinking requires a mindset shift, to abstract one level upwards. You need a different set of solutions for an individual problem vs the whole category; it's a different beast altogether to help one homeless person than to help all of them.

Learn more:

Evolutionary mismatch

Evolutionary traits generally change slower than the environment. Therefore, the traits that were once helpful can now be harmful because the environment is different. When this is the case, we talk of evolutionary mismatch.

While evolutionary mismatch can and does happen in animals and plants, humans are a prime example because our environment changes so rapidly.

- We evolved to value sweet and fatty foods. But now this trait is a disadvantage because sugary and fatty foods aren't scarce anymore - you can get them delivered to your door with one button.

- Our bodies evolved to be alert under stress, such as when hunting. But now we have chronic stress, and the constant alertness leads to burnout and health issues.

- We evolved to value newness: for example, a new female/male is a new chance at spreading your genes, or new information in the form of gossip is valuable in choosing who to trust or mate. But now we can get 10,000x the amount of newness and stimuli over the internet (social media, news, porn...), leading to addiction and mental health issues.

It is important to understand that we essentially have a hunter-gatherer brain and body in a modern society, so there is huge (and rapidly increasing) mismatch. Obesity, most health issues, most mental health issues, addiction, lack of meaning, loneliness... many negative matters of the body or brain can be due to evolutionary mismatch.

This is not to say that everything was perfect when we lived in huts and that everything is wrong now, but that we evolved in the former environment and therefore it is only logical that issues emerge when we live in environments we didn't evolve to live in. That's the idea behind evolutionary mismatch.

So if you have issues, that's not necessarily your fault. It's like blaming a penguin for not thriving in a desert.

Learn more:

Supernormal stimuli

Consider these findings from Tinbergen, a researcher who coined the term supernormal stimulus:

- Songbirds have light blue and small eggs. The exaggerated, supernormal version of those eggs would be a huge, bright blue dummy egg. When such a dummy is shown to the songbirds, they would abandon their real eggs and instead sit on top of the dummy; they choose the artificial over the real because the artificial is more stimulating.

- There's more: the songbirds would feed dummy children over their real children, if the dummies had wider and redder mouths. The children themselves would rather beg food from a dummy mother than the real mother, if the dummy had a more stimulating beak.

Supernormal stimuli are exaggerated versions of the things we evolved to desire. Supernormal stimuli hijack the weak spots in our brains by supplying so much of what we desire that we don't want the boring, real thing anymore. Thus, we act in evolutionarily harmful ways - much like the bird who abandons their eggs. When you can eat pizza, who wants broccoli? When you can have 500 porn stars, who wants a "normal" mate? Why bother with the real life, you have much more fun in the game world, with much less effort.

While there are physical superstimuli, like drugs and junk food, we must be especially careful with digital superstimuli because there is virtually no limit how much stimuli can be pumped into you. A pizza can include only so much fat and salt and other stuff that makes your brain go brrr... But there's no limit as to how stimulating a video or game or virtual world can be. Nature has set no ceilings; it has only determined what we are stimulated by, so we always want more, at all costs.

We're already approaching a point with VR porn and "teledildonics" where one may rather mate the technology than a real person. Some would much rather move a video game character than their real bodies. At some point, we'll maybe create artificial children (perhaps in the metaverse) who simply are much cuter than real babies, and much less trouble. As fewer and fewer people have babies - intentionally or unintentionally - we realize that we aren't much smarter than the birds sitting on huge blue balls instead of their own eggs. As I write in a longer post, superstimuli may be the thing that leads to human extinction.

Learn more:

Minority rule

Nassim Taleb popularized the idea of minority rule, where change is driven not by the majority but instead by a passionate minority. If something a minority insists on is fine with the majority, that generally becomes the norm.

For example, imagine you're a baker and want to sell buns. It doesn't make sense for you to make two sets of buns - one lactose-free and one "normal" - because everyone is fine eating lactose-free buns, but not everyone can eat your buns that include lactose. It's just easier to make everything lactose-free. So almost all pastries you find are lactose-free (at least in Finland).

It's key to notice the asymmetry at play: the majority must be quite indifferent to the change while the minority must be quite inflexible about it.

The idea of minority rule can be seen everywhere.

- Why we have pronouns next to people's names on social platforms and conference badges is not because the majority insisted on it, but because a very passionate minority did.

- Lunch in many cafés and restaurants is increasingly plant-based because vegetarians will take their money elsewhere otherwise, and non-vegetarians don't generally mind if their lunch has fewer meat options, or none at all on some days.

- In corporate life, you can usually change something if you're passionate enough about it. Most people don't really care that much, so if it's a deal-breaker for you, they'll let you change it (especially if they don't need to work on it).

Learn more:

Convergent evolution

Convergent evolution occurs when different species independently evolved similar features. For example, a bat, a fly and many birds have independently of each other evolved wings and an ability to fly.

This is much the same as human civilizations that hadn't been in touch with each other independently invented writing and the idea of stacking big bricks on top of each other in a pyramidic fashion. (No, there's no conspiracy - just convergent evolution.)

If you see the same pattern in independent groups, there's probably a reason for that pattern. If most flying animals developed wings, that's a good sign that wings are one of the best structures for flying. If most swimming animals like fish and dolphins have a similar, streamlined shape, that's probably the shape that works best in water.

Similarly, if you see a pattern repeating itself across disciplines, that's a sign that there's something to that pattern. Consider this tweet from Naval:

Convergent evolution is a validation mechanism.

Learn more:

Compulsion loop